Nearly 1,000 Cargos: The Legacy of Importing Africans into Charleston

Processing Request

Processing Request

Between 1670 and 1808, nearly 1,000 cargos of enslaved Africans entered the port of Charleston. This fact represents one of the most important chapters in the history of our community, but we the people of 21st century Charleston still struggle to wrap our collective brains around this weighty topic. How can we tell this important story to our children and to the millions of visitors who come here each year? Today, I’d like to share with you an outline of my own efforts to corral some obscure facts into an illuminating story.

Working as a public historian in Charleston over nearly two decades, I’ve fielded a lot of questions from locals and visitors about the history of Sullivan’s Island, especially concerning its “pest house(s)” and the island’s role in the trans-Atlantic slave trade of the eighteenth century. More recently, I’ve also heard a lot of questions about the history of Gadsden’s Wharf, the site of the new International African American Museum, and the historic role that ground played in the landing of African captives. At first, I had very little information under my cap about these topics to offer to local audiences. I was aware of a certain amount of scholarship relating to their respective histories, but I had never made a concerted effort to locate new data that might enhance the existing conversation. Nevertheless, as a regular part of my job (and for recreation), I routinely spend a lot of time in local archives reading primary source materials, especially the public records produced during what we might call South Carolina’s “long” eighteenth century (that is, from the reorganization of our General Assembly in 1692 to the beginning of the War of 1812).[1] In the course of this ongoing, systematic research, trolling primarily for information related to topics such as fortifications and militia activities, I began making notes about other interesting stories and topics that I encountered. For example, the governor interrogating Spanish prisoners of war, or legislative debates about the “pirates of the Bahamas,” and a host of other matters that provide valuable details to help us reimagine Charleston’s early history. Among the interesting sidelines that caught my attention were references to quarantine practices, which frequently (but not always) included Sullivan’s Island and its successive “pest houses,” as well as occasional doctors’ reports about shiploads of newly-arrived immigrants and enslaved Africans. I made notes about such references and continued my journey of archival exploration, thinking that one day I might have a sufficient quantity of data to fill an interesting lecture or two. As my archival tour progressed and my body of notes grew larger, however, I realized that some of the data I had gathered did not quite match the historical narrative I had heard about topics such as Sullivan’s Island. Here began a professional conundrum: whether to keep this divergent data to myself, or to offer it to the public and rock the boat.

Over the past few years, I have presented a number of public lectures, both here at CCPL and elsewhere in the community, in which I’ve tried to summarize and narrate the historical data I’ve collected about Sullivan’s Island, its successive “pest houses,” Gadsden’s Wharf, and related topics. Although my findings differ slightly from the popular narrative published and espoused by other historians, the feedback I have heard from audiences has been generally positive and supportive. These are topics about which a lot of people clearly have a significant interest, but I did not enter into this field with a particular agenda or goal; rather, I had simply collected some historical data and wanted to share with anyone interested in the topic. Having done so on several occasions, I began hearing questions about when I was planning to publish my findings. To be honest, I never imagined that this work would develop into something publishable, and I already have far too many publishing projects in the queue. Nevertheless, the idea started to grow on me, and I began thinking about drafting an article about Sullivan’s Island and its pest houses.

In the course of the past year, I’ve been struggling to construct a summary of my research. Rather than simply narrating the data in chronological sequence can calling it done, I feel compelled to position this information in a robust historical context, in order to facilitate its accessibility to a wider audience. My efforts to construct this contextual frame have been frustrated, however, by the gnawing feeling that I was missing something important. After months of head-scratching, I believe I’ve found a solution to my own methodological conundrum. This is not simply a matter of calculating how many people landed on which island or wharf. Places such as Sullivan’s Island and Gadsden’s Wharf represent parts of a larger local system of protocols and logistics that in turn formed the final links in a much longer chain of trans-Atlantic commerce. This project is going to require more of my time than I ever expected, but I’m convinced that it’s an important endeavor that merits serious attention. In the following paragraphs, I’d like to share with you a preview and outline of this project as I currently conceive it.

In the course of the past year, I’ve been struggling to construct a summary of my research. Rather than simply narrating the data in chronological sequence can calling it done, I feel compelled to position this information in a robust historical context, in order to facilitate its accessibility to a wider audience. My efforts to construct this contextual frame have been frustrated, however, by the gnawing feeling that I was missing something important. After months of head-scratching, I believe I’ve found a solution to my own methodological conundrum. This is not simply a matter of calculating how many people landed on which island or wharf. Places such as Sullivan’s Island and Gadsden’s Wharf represent parts of a larger local system of protocols and logistics that in turn formed the final links in a much longer chain of trans-Atlantic commerce. This project is going to require more of my time than I ever expected, but I’m convinced that it’s an important endeavor that merits serious attention. In the following paragraphs, I’d like to share with you a preview and outline of this project as I currently conceive it.

Although the legal importation of enslaved people ended more than two centuries ago, Charleston’s historic role in this business represents a burdensome legacy that weighs heavily on the local conscience and influences our stewardship of the historic landscape. For a variety of reasons, some members of this community are compelled to advocate for a more robust understanding of the experiences endured by the African captives who once disembarked in Charleston, and to provide an accurate interpretation of that story to the millions of visitors who travel to this area each year. To do justice to this important legacy, such efforts must begin with a foundation composed of empirical, verifiable data. The documentary evidence related to Charleston’s role in the trans-Atlantic slave trade is plentiful but incomplete, and it is scattered among disparate archives. The work of collecting the necessary evidence is an ongoing endeavor, undertaken by a number of individuals, agencies, and institutions, both locally and abroad. To understand the significance of the local picture, we have to first back up to see the larger scene, and position Charleston within the landscape of an international trade network.

Thanks to the work of numerous scholars in the course of the last century, historians now have a good understanding of the enormous scale of the business of transporting African captives to the New World over a span of more than 350 years. The paper trail of that terrible trade, which commenced in the early 1500s and continued into the 1860s, survives in documents found in a number of archives scattered around the globe, in places like London, Liverpool, Sierra Leone, Lisbon, and Rio de Janeiro. Based on figures drawn from careful studies of this documentary record, the scholarly community now accepts that more than ten million of the approximately twelve million people forcibly removed from Africa survived the horrific “middle passage” across the Atlantic Ocean and landed at a number of destinations in the New World. The majority of these slave cargos sailed to ports in South America and the Caribbean Sea, but approximately 400,000 Africans captives came to various ports on the mainland of North America. Of that total, we know that approximately 150,000 to 200,000 Africans passed through the port of Charleston, in nearly 1,000 separate cargos, between the founding of the Carolina colony in 1670 and the legal prohibition of the trans-Atlantic slave trade enacted by the United States Congress in 1808. These numbers demonstrate that Charleston received a greater share of the trans-Atlantic slave trade than any other port in mainland North America—approximately forty percent (40%) of all the Africans captives brought to this continent—and clearly establish this port as a site of great importance in the broad historical narrative of the African-American experience.

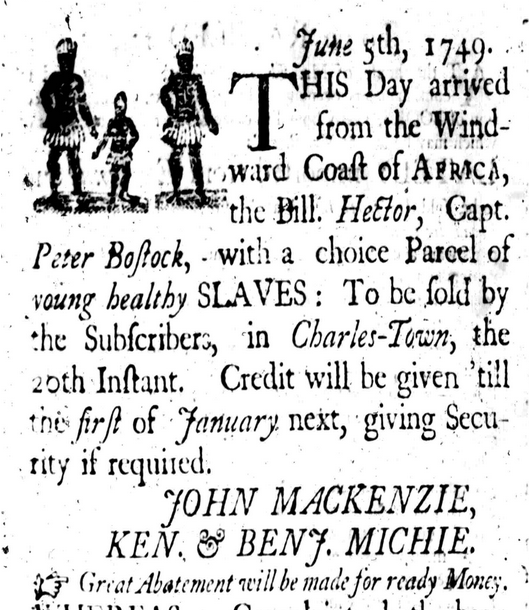

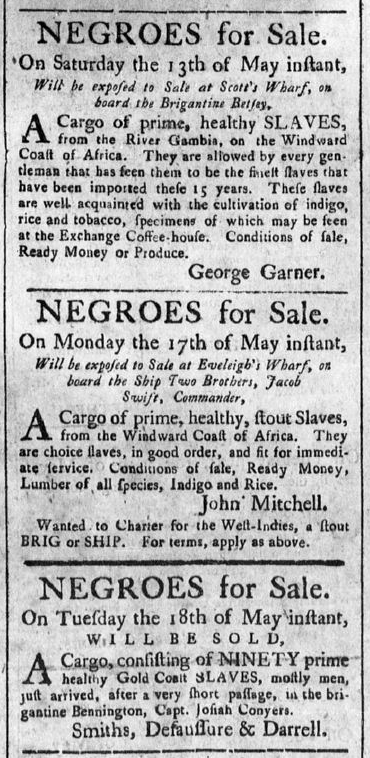

The investigative work of compiling the evidence necessary to construct this broad profile of the trans-Atlantic slave trade has involved many people working over the last century in a variety of archives around the globe. The well-respected website slavevoyages.org, for example, represents the work of international researchers striving to document the movement of thousands of ships and millions of people involved in the trans-Atlantic slave trade between the years 1514 and 1866. Similarly, a number of historians have focused specifically on the North American scene, studying the individuals and institutions in colonial America and, later, the United States that financed, insured, and defended this traffic in human cargo between 1619 and 1808. Closer to home, documentary resources housed in South Carolina archives provide valuable insight related to the entry of slave ships into Charleston harbor, the sale of their African cargos, and the lives of the enslaved people whose labors and cultures played such a large role in building this community and this nation.

The investigative work of compiling the evidence necessary to construct this broad profile of the trans-Atlantic slave trade has involved many people working over the last century in a variety of archives around the globe. The well-respected website slavevoyages.org, for example, represents the work of international researchers striving to document the movement of thousands of ships and millions of people involved in the trans-Atlantic slave trade between the years 1514 and 1866. Similarly, a number of historians have focused specifically on the North American scene, studying the individuals and institutions in colonial America and, later, the United States that financed, insured, and defended this traffic in human cargo between 1619 and 1808. Closer to home, documentary resources housed in South Carolina archives provide valuable insight related to the entry of slave ships into Charleston harbor, the sale of their African cargos, and the lives of the enslaved people whose labors and cultures played such a large role in building this community and this nation.

Because of the nature of the surviving documents, the body of scholarship surrounding the history of the trans-Atlantic slave trade is generally broad and impersonal. Historians have made good use of the extant evidence, which consists mostly of business records, to reconstruct the economic and political networks that facilitated the slave trade, but this material, by its very nature, includes very few local or personal details. This observation is not intended as a judgment on the existing scholarship—it’s simply a statement of fact. But herein lies the problem. As a public historian talking with individuals and audiences around this community, I frequently encounter people who want to learn specific local details about the experiences of the Africans who arrived in Charleston harbor. Where did they land? How were they treated? Where were they sold? Unfortunately, there are no surviving narratives written by survivors of the passage from Africa to Charleston, and precious few records that even come close to helping us understand the experience from their subjective viewpoint. Our ability to re-imagine the horrors of that journey is permanently abridged by the paucity of surviving documents. Thanks to the disappearance and destruction of other important historical records, we will never be able to reconstruct the details pertaining to the arrival, debarkation, and sale of slave cargos in Charleston harbor with a high degree of precision. At best, we might be able to construct an outline of the general experiences common to all of the nearly one thousand cargos of African captives that entered Charleston harbor between 1670 and 1808. But where does such work begin?

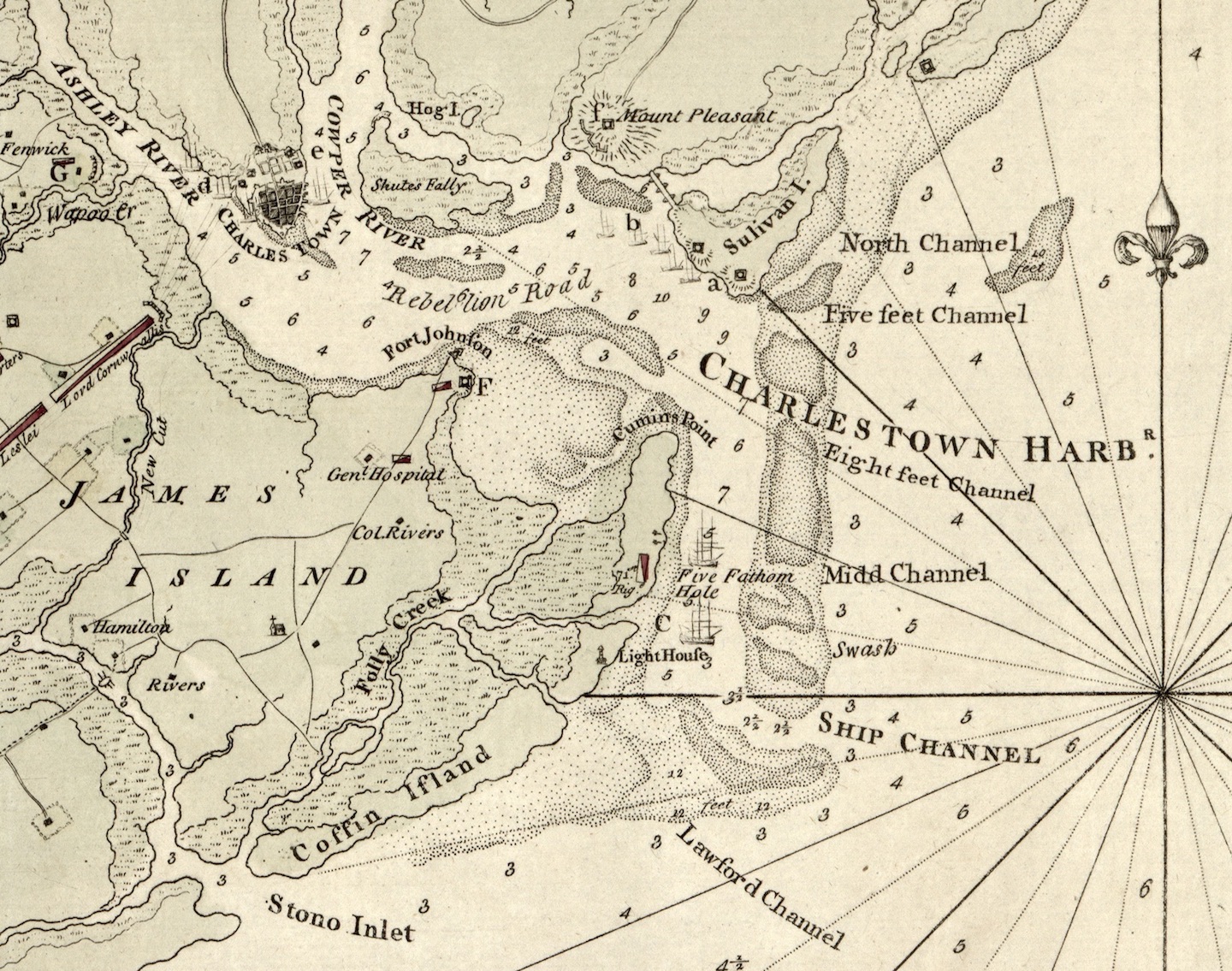

To date, historians and other writers addressing the eighteenth-century traffic of African captives into the port of Charleston have focused much of their attention on Sullivan’s Island, a coastal barrier island situated at the northeast edge of the harbor. Frequently described as the first point of landing for most of the Africans brought to this port, Sullivan’s Island emerged as an important theme in African-American history after 1974, when the eminent historian Peter Wood suggested that “it might well be described as the Ellis Island of black Americans.”[2] Over the past half-century, the story of incoming African captives landing on Sullivan’s Island has evolved from an obscure footnote on the periphery of colonial American history to a familiar part of mainstream conversations about the history of South Carolina and of the African-American experience in general. Visitors to present-day Charleston often hear that some, most, or even all of the African captives brought here were landed first at Sullivan’s Island, where they performed a temporary quarantine at a site called a “pest house” before being taken to the wharves of Charleston for sale. Variations on this story abound in published literature, websites, documentary films, bronze markers, and ephemeral speeches about Charleston and its historical involvement with the trans-Atlantic slave trade. The wording of some versions of this story is conservative, such as a printed bulletin provided by the National Park Service at Fort Moultrie that states “a portion of these captives served quarantine, but how many Middle Passage survivors set foot on Sullivan’s Island is unknown.” Other claims are quite bold, such as the text of the plaque installed on the island by the Toni Morrison Society in 2008, which asserts that “nearly half of African-Americans have ancestors who passed through Sullivan’s Island.” As a result of such publicity, Sullivan’s Island has become the site of commemorations and a place of pilgrimage for people—black and white, local and foreign—who wish to meditate on the fate of the men, women, and children who either survived or died during the horrific “middle passage” between Africa and the port of Charleston.

To date, historians and other writers addressing the eighteenth-century traffic of African captives into the port of Charleston have focused much of their attention on Sullivan’s Island, a coastal barrier island situated at the northeast edge of the harbor. Frequently described as the first point of landing for most of the Africans brought to this port, Sullivan’s Island emerged as an important theme in African-American history after 1974, when the eminent historian Peter Wood suggested that “it might well be described as the Ellis Island of black Americans.”[2] Over the past half-century, the story of incoming African captives landing on Sullivan’s Island has evolved from an obscure footnote on the periphery of colonial American history to a familiar part of mainstream conversations about the history of South Carolina and of the African-American experience in general. Visitors to present-day Charleston often hear that some, most, or even all of the African captives brought here were landed first at Sullivan’s Island, where they performed a temporary quarantine at a site called a “pest house” before being taken to the wharves of Charleston for sale. Variations on this story abound in published literature, websites, documentary films, bronze markers, and ephemeral speeches about Charleston and its historical involvement with the trans-Atlantic slave trade. The wording of some versions of this story is conservative, such as a printed bulletin provided by the National Park Service at Fort Moultrie that states “a portion of these captives served quarantine, but how many Middle Passage survivors set foot on Sullivan’s Island is unknown.” Other claims are quite bold, such as the text of the plaque installed on the island by the Toni Morrison Society in 2008, which asserts that “nearly half of African-Americans have ancestors who passed through Sullivan’s Island.” As a result of such publicity, Sullivan’s Island has become the site of commemorations and a place of pilgrimage for people—black and white, local and foreign—who wish to meditate on the fate of the men, women, and children who either survived or died during the horrific “middle passage” between Africa and the port of Charleston.

Similarly, the site of Gadsden’s Wharf on the Cooper River in downtown Charleston has received a great deal of attention in recent years. The long-proposed International African American Museum, now on the verge of breaking ground, will soon rise above a spot of waterfront turf where tens of thousands of disembarking African captives commenced their American lives. The historical significance of that site on Gadsden’s Wharf is beyond question, but confusion persists over the number of Africans landed there. We might never be able to determine the precise number, but, with the help of data extracted from a broader range of historical resources, we can close the gap and arrive at a well-reasoned estimate. Like Sullivan’s Island, Gadsden’s Wharf is poised to become a site of pilgrimage and reflection. As the residents of the larger Charleston community seek to improve and expand the historical narrative we tell ourselves and to those who visit us, I believe it is incumbent on us to dig deeper in the historical record and work toward constructing a fuller and more accurate story.

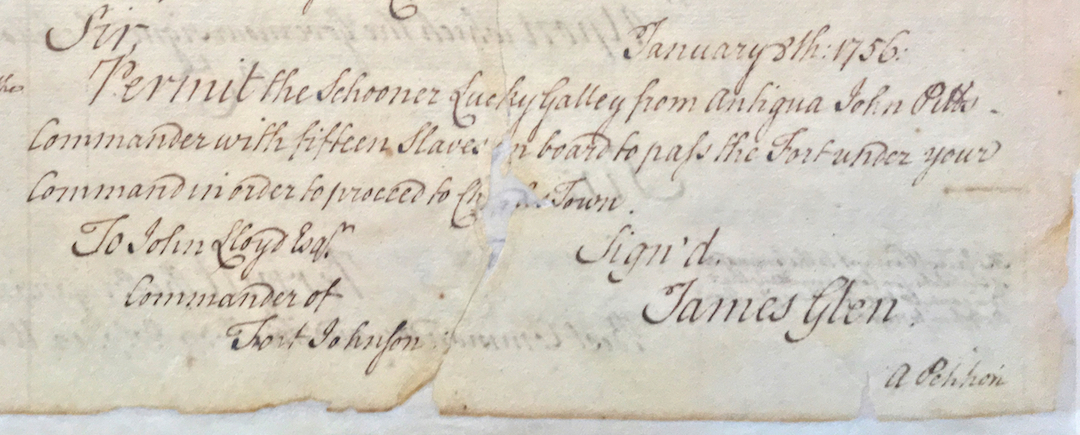

In order to gain a better understanding of the role of specific topics such as Sullivan’s Island, its pest houses, Gadsden’s Wharf, and similar sites, I believe it’s necessary to view these individual sites as component parts of both a broader landscape that encompasses all of Charleston harbor and a broader logistical and legal process. Just like the cargo ships entering Charleston harbor today, the trans-Atlantic vessels that once brought African captives to Charleston were obliged to follow a series of legal protocols imposed on the arrival and movement of valuable assets into and across the geography of Charleston harbor. In order to see the relevance of this comparison, and to understand the logic behind their collective movements into and across the harbor, it is important to recognize that all of the African captives brought into the port of Charleston for the purpose of sale were considered cargo rather than passengers. As such, the story of their movements in the first days of their American experience followed the same trajectory as all other imported commodities, living and inanimate. Once we acknowledge that these Africans represented a sort of cargo to the people that held them in bondage, it becomes easier to recognize that this human cargo was part of a business, which was governed by a system of legal protocols and followed a series of logistical steps within a confined geographic space.

In order to gain a better understanding of the role of specific topics such as Sullivan’s Island, its pest houses, Gadsden’s Wharf, and similar sites, I believe it’s necessary to view these individual sites as component parts of both a broader landscape that encompasses all of Charleston harbor and a broader logistical and legal process. Just like the cargo ships entering Charleston harbor today, the trans-Atlantic vessels that once brought African captives to Charleston were obliged to follow a series of legal protocols imposed on the arrival and movement of valuable assets into and across the geography of Charleston harbor. In order to see the relevance of this comparison, and to understand the logic behind their collective movements into and across the harbor, it is important to recognize that all of the African captives brought into the port of Charleston for the purpose of sale were considered cargo rather than passengers. As such, the story of their movements in the first days of their American experience followed the same trajectory as all other imported commodities, living and inanimate. Once we acknowledge that these Africans represented a sort of cargo to the people that held them in bondage, it becomes easier to recognize that this human cargo was part of a business, which was governed by a system of legal protocols and followed a series of logistical steps within a confined geographic space.

The arrival of slave ships into the port of Charleston represented the final links in a much longer chain of trans-Atlantic commerce. Using our business lens to view the tail end of this journey, we might identify the two principal branches of the process as “arrival” and “sale.” Each of these topics can be further divided into smaller themes, including pilotage, inspection, quarantine, entry, advertisement, preparation, auction, and delivery. For each step, we can identify a set of legal parameters and practices, a number of actors, and a set of geographic locations. It is my hope that this work will create an intellectual framework that will improve our understanding of the contributing role of locations such as Sullivan’s Island, Gadsden’s Wharf, and many others. Simultaneously, I believe this exercise will provide us with a general temporal and geographic outline that will help us appreciate the experiences endured by the nearly 200,000 people who entered Charleston harbor in bondage.

I haven’t finished writing this material, and I haven’t even finished collecting the necessary data. Having now settled on a methodology for this project, however, I feel confident that I’m on a viable path and I’m ready to get started. In the coming months, I plan to present an ongoing series of periodic installments that will eventually (after a couple of years) coalesce into a proper book. The final product will be more than just a compilation of podcast-sized chunks, of course, but the present format works well for tackling a big subject in a series of installments. By way of preview, I’ll just mention a few of the themes you can expect to hear about in upcoming episodes:

First, we’ll talk about the entry of commercial vessels into Charleston harbor, and how the relatively simple act of “crossing the bar” triggered a series of mandatory transactions and duties that were prescribed by law and enforced by a number of agents on behalf of the local government. Here we’ll learn about the role of pilots, searchers, waiters, collectors, signal flags, and the guns of Fort Johnson.

Next, we’ll delve into the convoluted history of local quarantine law; that is, the legal protocol enacted by the government of South Carolina to prevent the introduction of contagious diseases that might be carried by people—Africans and Europeans—arriving from abroad. Here we’ll learn about the cooling of heels and the stretching of legs, the use of smoke and vinegar, the delivery of food, water, and clothing, and the opposing efforts of local merchants and physicians.

We’ll also explore the geography relevant to this story, including the several physical sites and structures in and around Charleston harbor that were used for the anchorage, quarantine, landing, and sale of slave cargos. This endeavor will encompass such familiar places as Sullivan’s Island, Fort Johnson, and Gadsden’s Wharf, as well as a variety of less-familiar wharves and now-obscure place names such as Rebellion Road, the ironically-named “Point Comfort,” and a colonial-era auction site commonly known as “the usual place.”

Layered on top of each of these sub-plots is, of course, the main theme of this entire exercise: the arrival of nearly 200,000 African captives in nearly one thousand cargos between the years 1670 and 1808. During the course of that entire time span, each of the storylines I just mentioned was a fluid narrative that changed over time according to a variety of circumstances both local and trans-Atlantic. Describing the role of a place like Sullivan’s Island or Gadsden’s Wharf within this multi-layered, dynamic narrative is, therefore, like trying to hit the proverbial moving target. In my mind, getting a solid grip on the larger context will help us to see the important facts more clearly. But that’s just my personal methodological solution. For those of you who really care about this topic, I hope today’s program didn’t seem like an unnecessarily complicated, overly-academic exercise. My explanation might seem pedantic to some, but I hope the goal is clear: I want to marshal the surviving documentary evidence related to this terrible business in way that helps us to honor the memory a large body of people whose names are almost entirely lost.

[1] At the South Carolina Department of Archives and History (SCDAH) in Columbia, I’ve made a systematic tour through all of the surviving manuscript legislative journals (including the journals of the Grand Council, Commons House, Upper House, His Majesty’s Council, Privy Council, House of Representatives, and Senate) from the beginning of the Carolina colony to about 1817. At SCDAH and at CCPL, I’ve studied all of the statutes and ordinances of our provincial, state, and local governments up to 1865. At CCPL and at the Charleston Library Society, I’ve read through all of the surviving Charleston newspapers from 1732 up to about 1875. While employed at the South Carolina Historical Society, I read through most every box of private papers housed at the South Carolina Historical Society. At present, I continued to re-visit these sources for clarification and search for additional materials on a regular basis.

[2] Peter Wood, Black Majority: Negroes in Colonial South Carolina from 1670 through the Stono Rebellion (New York: W. W. Norton, 1974), iv. Professor Wood was not the first historian to draw attention to this aspect of Sullivan’s Island history, but the widespread and lasting influence of his 1974 book contributed greatly to the dissemination of this story.

PREVIOUS: Under False Colors: The Politics of Gender Expression in Post-Civil War Charleston

NEXT: The Forgotten Akin Family of Charleston

See more from Charleston Time Machine

- Log in to post comments